In the Path of Destruction

I started a post last week about volcanos, then I got sick, so here it is now. I was inspired to write this because I follow the United States Geological Survey (USGS)and the American Geological Society on Facebook. The 18th of May was the 25th anniversary of the Mount St. Helens eruption. Both organizations ran daily posts about the most violent volcanic eruption in the continental United States in recorded history.

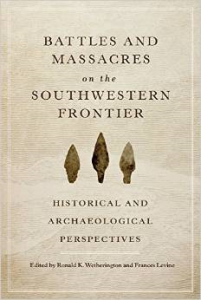

The USGS quoted extensively from In the Path of Destruction, a book about the events around the eruption. That eruption in1980 was the most violent volcanic eruption the United States has experienced in recorded history.

Close to some big cities but relatively isolated, only about 56 people were killed. The low death toll was also a result of the Forest Service, the local county sheriffs, and Weyerhauser Timber restricting access to the area around the mountain, a popular recreational area.

In the Path of Destruction has two sections, narratives of events before and during the eruption, and many eyewitness reports collected by author Richard Waitt, a USGS geologist present at Mt. St. Helens starting in March 1980, when the volcano started coming alive and throughout the eruption and aftermath. Three weeks after the eruption he was in a bar talking to a man who had lived through the eruption and realized the stories of witnesses could add to scientific knowledge of the event.

This book is one you lose sleep over. Do you remember May 18, 1980? Those people do, their memories are as vivid now as my memory of the day Kennedy was shot. Waitt interviewed a wide range of people from USGS geologists, pilots in the air nearby when it blew, campers, loggers, and local residents who survived. Their stories are why the book kept me awake. The author’s narratives are well researched and written. He puts the science, events, and the human story into a book that will hold even those who are not geology geeks.

In fact as a geology geek, I found myself wanting more science. That is probably good for most readers. A big part of the story is the unusual behavior of the volcano before it blew. There were hundreds of earthquakes in the two months before the big eruption, accompanied by venting, minor ash falls, and the formation of a small crater. The strangest phenomenon was the formation of a huge bulge on the north side of the mountain.

The bulge grew about five feet every day, accompanies by swarms of small earthquakes some of the USGS people thought were from magma intruding into the bulge. The bulge grew, with vertical cracks forming on its face. Some thought a major eruption was imminent, others thought it would be a relatively minor event. Politics kept moving the roadblocks back and forth, with logging being allowed outside the immediate danger zone. It’s tough enforcing a roadblock with logging trucks coming out of the closed area.

In 1980, eruptions could not be forecast. In 2015, earthquakes can’t be forecast. People wanted in the closed area to go to their cabins, to hike, camp, and fish. We think of volcanic eruptions going up from a crater at the summit. On May 18th, a magnitude five earthquake caused the bulge to slide. That caused the mountain above the bulge to slide.

The accounts of the survivors and witnesses of the eruption are what make the book so gripping. For me events thirty five years ago came alive. I won’t go into any of the stories. Read for yourself. The photographs and maps provide a useful context and show the eruption as it happened. I continue to be astounded that one plate smashing into another at the rate your fingernails grow can produce events like volcanic eruptions and earthquakes like the one in Nepal. There is lots of really hot stuff down there in our Earth, and if the crust gets weakened, here it comes.

A few weeks ago I was headed east from Gunnison up the Tomichi Creek valley. The rocks looked sort of like sandstone, so common here in Colorado, but they just didn’t look right. It dawned on me. Volcanic tuff, just like the ash that blew out of Mt. St. Helens. It happened here and in geologic terms, not that long ago. Maybe 65 million years ago, give or take.