Bad Water Part Two

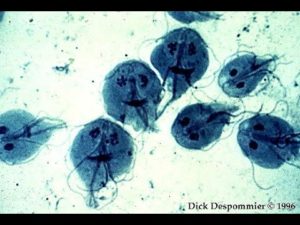

Let’s continue with stories about what happens when pathogenic organisms get into a potable water supply. Usually the causes of disease outbreaks are caused by no treatment or failure of the treatment process. This one, however, is because of a cross connection.

Cross connections are when a treated water system is contaminated by water coming into it downstream of the treatment plant. Garden hoses are a good example. If the sprinkler head is in a puddle while in use and a negative pressure occurs, contaminated water can be sucked Into the piping system. Opening a fire hydrant in the area is a common cause. Flow in the water main increases and the venturi effect can pull water from the garden hose into the main. In big buildings, bad plumbing can let boiler or air conditioning into the building plumbing system.

Fort Collins, Colorado had a major cross connection event before I went to water-wastewater school there. The lab people at the wastewater plant got a phone call one weekend. The caller said several people in her neighborhood around City Park had gotten sick in recent days. They went right out and sampled in several places. Sure enough, the drinking water had coliform bacteria, a sure indicator of fecal contamination. Much fire hydrant flushing ensued and a boil order went into effect. All the testing indicated the water was still bad around City Park. It occurred to someone to check with the Parks Department. The park was irrigated with water from City Park Lake. There were times when irrigation demand exceeded flow onto the lake and city water was used to supplement the ditch water. This is from memory. No online references.

There are backflow preventers to keep the systems separate. You have seen those big brass devices in parks in your area. Another method is an air gap. City water drops out of a pipe above a tank where the water is collected and pumped out. The air gap keeps things safe. Well, the old tank had rusted out and someone just put in a piece of pipe. Lake water into city water. There are lots of wild geese in Fort Collins using that lake. Fecal-oral.

If you have been to New York, you have seen all those old water tanks on the top of buildings. City water is pumped into the tank then the water is contaminated by sediment accumulated on the bottom of the tank or a hole allows birds and animals to enter the tank.

The worst example of a tank getting contaminated occurred many years ago in a water district south of Colorado Springs. The maintenance people entered the hatch in the top of a several million gallon storage tank and discovered a dead body floating there. No diseases had been reported, verifying the old water adage “The solution to pollution is dilution.” I did a Web search on this event. For some reason, there is not a word online.

The worst example of a tank getting contaminated occurred many years ago in a water district south of Colorado Springs. The maintenance people entered the hatch in the top of a several million gallon storage tank and discovered a dead body floating there. No diseases had been reported, verifying the old water adage “The solution to pollution is dilution.” I did a Web search on this event. For some reason, there is not a word online.

Years later, the city of Alamosa, Colorado found coliform bacteria in the city water. A boil order went into place and the search began. The local water department was overwhelmed and Denver Water sent a team to help. Much searching led to discovering the bad stuff was coming from a big storage tank that had seen no maintenance in years. Usually storage tanks are regularly taken out of service and cleaned. With Denver Water it is an annual practice. That Alamosa tank had a lot of sludge on the bottom and a hole just under the roof where birds were entering. Again, fecal-oral.

My experience along this line was when I was working at the Greeley, Colorado wastewater plant in the spring of 1979. The Cache La Poudre had a huge spring runoff. The flood washed out a pipeline in the plant that moved raw wastewater across the river. The city’s untreated sewage went into the river for several days until an emergency pipeline was built. The solution to pollution was in effect because flow in the river was at record levels.

Early in the twentieth century, many cities built primary wastewater plants to provide some treatment. The wastewater went into big settling tanks where a lot of the solids were removed and the remainder went to the river. Greeley did that. There was an old pump that handled the sludge that went into service in 1926. Secondary treatment came in, but during World War II, many systems shut the secondary systems down to conserve electric power. Partly treated sewage in the river all over the country. When the Poudre flooded, we had to wear hip boots around the plant. The door to that old pump station was sandbagged to keep the river out. The whole thing got rebuilt just as I left Greeley for Manitou Springs and away from wastewater plants.

Growing up in Fruita, Colorado in the 1950’s, my friends and I roamed all over the town. Just southwest of town we were exploring a natural wash and discovered the sewage outfall for the town of Fruita, population 1800. Raw sewage went into the wash and to the Colorado River a mile downstream. Gross. There were lots of what we called in the wastewater trade “white trout” hanging from the bushes. Some years later, the town built a sewage lagoon to treat the wastewater.

Well, I think I have given you enough horror stories