Dramatic

Rattlesnake Canyon is near Fruita, Colorado, where I grew up. My friends and I ran all over the hills north and west of the Colorado National Monument, but I had never been to

Rattlesnake Canyon. It is a bit too far for kids on foot. We got into the canyons just east of the canyon, now part of the Black Ridge Wilderness, but I did not know about the arches in Rattlesnake Canyon.

Close to town, the canyon is a bit tough to get to. The Pollock Canyon trailhead near the river means an overnight backpack to do justice to the country. The other route follows Black Ridge west from the Glade Park Store, and is for 4×4 vehicles or Subarus you are willing to bash around. From the trailhead it is about four miles on the trail if you take the shortcut.

I have rambled around the Colorado Plateau off and on all my life. From the Grand Canyon to Dinosaur and from the Grand Hogback to the Wasatch, the plateau offers some

Rattlesnake Canyon

of the most magnificent country anywhere. Rattlesnake Canyon is up there with the best. Arches has more arches, and there are bigger canyons (not that many), but Rattlesnake has it all. The real bonuses are that it is close and not cluttered up with people. With the exception of Grand Canyon, most anywhere else offered some solitude at one ime. No longer. Thirty miles from Grand Junction, with a competent high clearance vehicle you can be in wilderness in view of Fruita.

Ah, the sense of space. I live in the city and it is impossible to have a sense of space, even with Mt. Evans looking down at you. From those canyon rims the expanse opens my mind. Grand Mesa, the Bookcliffs, and the Roan Cliffs rim the Grand Valley, quite a scene by itself.

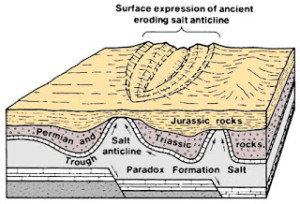

The canyon walls are Wingate sandstone capped by harder Kayenta sandstone. That cap rock forms a bench with the Entrada sandstone (slickrock) set back from the rim. Rim Rock Drive in the Monument is mostly on that bench, and the trail to Rattlesnake drops down on the bench and curves around the canyon rim to the arches. The arches are in the slickrock, ancient sand dunes turned to stone. It is easy to see the rounded dunes in the rock. Erosion works its way into the cliffs following the curve of the dunes, forming alcoves. As the alcoves erode farther, sometimes the back of the alcove drops out, leaving an arch. I saw six of them. Arches in Colorado, the second largest concentration in the country, maybe the world.

About that trail. I got away from Denver at 6:00 AM, not my best time of day. I filled my water bottle and left it on the kitchen counter. I didn’t realize it until I was at the trailhead at about 1:30 PM. I am also out of shape, my exercise restricted by a couple of broken ribs for five weeks. Have I mentioned that I am 72 years old and impulsive? I looked at the sign, 3 1/2 miles. It was only 90 degrees or so, a piece of cake.

First Arch. Where I climbed up the rock through the arch.

I covered about half of the trail when I realized I was getting a bit dry. “Keep going, I can drink later”. The arches were a progression along the bench and close to the trail. With that row of arches on one side and that magnificent canyon with 400 foot sheer walls branching into side canyons on the other side, I was literally staggered by the beauty. Well maybe the stagger was because I was tired and thirsty. I caught up to a party of six people at the last arch, known as First Arch. At First Arch was the sign saying End of Trail. I didn’t know that, and by that time I was stopping to rest fairly often, so while resting I watched the party climb up the slickrock through the arch. I knew the trailhead was only about 1/2 mile from the arch. So, it was climb up the rock through that impressive arch or backtrack 3 1/2 miles. I climbed.

I have done a lot of sandstone climbing, and used to be pretty good at it. That was when I wasn’t 72, tired, getting sore, and thirsty. I climbed anyway. I would do about 20 feet, catch my breath, figure out my next moves, and climb again. The proper way to climb that stuff is on your feet even if it is steep. Feet have more traction than denim, and the work is easier than trying to slither up. I slithered. I was too weak to trust myself trying to walk up those steep slopes.

The rock has curves, little depressions, some tiny ridges, notches, and hollows to give one a way up. I tried to pick the easiest route, but it was still pretty steep. My knees paid the price, getting some good scrapes. Up on the rim, that last half mile was tough. It was uphill, but not too bad. I stopped twice and flopped down in the shade for a few minutes while walking slowly back to the truck.

There was about 1/4 of a cup of coffee in the truck that sure tasted good. I was lightheaded and pretty wobbly during the drive out. I stopped at the Visitor Center in the Park and drank water for a while. I got a motel room in Fruita about 6:00 PM, didn’t eat dinner, and drank water until lights out about 9:30.

Sunday morning I had breakfast, drank water, and took the scenic route back to Denver. I drank water and went up Plateau Creek to Collbran, went over Grand Mesa to Paonia where I had lunch and drank water, then over McClure Pass to Glenwood and home on I-70. I was fully rehydrated by Monday.

I didn’t see a rattlesnake in Rattlesnake Canyon

After a few minor incidents in the backcountry over the years, I have developed several rules to follow when Out There. Take water. Take enough water for the other persons you come across who didn’t bring enough water. Be in shape. Research where you are going so you know what to expect. Have a map. Carry the ten essentials in case you get into trouble. Tell people where you are going. You really should not go alone. I broke every rule.

What the fuck is wrong with me? I know. I am an impulsive ADD. When I got to the trailhead and saw I had no water I should have driven out. But, I wouldn’t have this story to tell. What I did do right was pace myself, not panic, and take my time getting out. It is just that my brain didn’t kick in until three hours too late.