Plate Tectonics

As a Western Colorado Native, having lots of geology looking down on me sparked my interest in the field. I have to know, so knowing how the Bookcliffs, Grand Mesa, and the Colorado National Monument got there stirred my curiosity. Plate Tectonics is responsible for that stuff poking up all over the place.

Back in the Permian when I took geology at Mesa College, the orthodox explanation for mountain building was something called isostasy. Push down in one place, and something will pop up nearby. New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta is sinking under the weight of all that mud coming down the river. New England is rising a little because that heavy glacial ice sheet melted. Geologist tried to make isostasy work in places like California with little success.

The early twentieth century saw some new thinking. Alfred Wegener proposed that continents move around on our sphere. He was laughed at when he gave papers on the idea. Yes, Africa and South America look like they once fit together, but how can an entire continent move? That is a lot of mass to be sliding around.

In the nineteen sixties new thinking started to change attitudes. Why are there identical fossils on the African and South American coasts? The real game changer came when oceanic exploration found the mid-oceanic ridges with young basalt near the ridges and steadily getting older farther away. The only explanation was a spreading seafloor. Things are on the move.

After college I subscribed to Scientific American magazine. It seemed like a new article appeared every month explaining how physical features are the result of magma (molten or hot and plastic rock) on the move. There are seven big (North America, Asia) plates and a number of smaller ones being affected by the rock coming from that spreading seafloor.

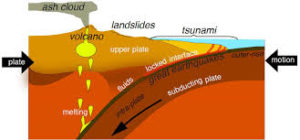

As the oceanic sea floor impacts the boundary of a continent, something has to give. The more dense seafloor basalt tends to dive under the continent. They can form trenches almost seven miles deep next to a subduction zone where the plate dives under the lighter rock of a continent. The subducting rock is wet, and changes chemically forming lighter rock that often belches up as volcanos. Earthquakes occur as the plates bump against one another, dip, or slide.

The island arcs off Asia are the current example. Java, the Philippines, Japan, New Guinea are all volcanic islands getting ready to smash into Asia. India already has, creating the Himalayas at the suture. Lots of shaking there, too.

Around 1.75 billion years an island arc docked (yes, geologists use that word) on the Wyoming Craton. The craton has some rocks as old as six billion (abbreviated as 6 ga) years old. Many of the rocks are around 3 ga. The oldest Colorado rocks are around 1.75 ga. Just outside Morrison, Colorado is the Great Unconformity. The red rocks are about 60 ma (million years). The dark gneiss and schist just barely up Bear Creek canyon are those 1.75 ga guys. Lots went on between those dates, but there it is all eroded away.

The Snowy Range in Wyoming is a result of the join-up. The coastal ranges in California that like to shake and burn and belch fire and rock formed from the collision of the Pacific and North American plates. As you are probably aware, L.A. is headed for Anchorage. Don’t worry it’s going to take a while.

The Rocky Mountains are kind of a strange story. Usually mountain building occurs at plate boundaries, like the Andes and the Cascades. What is known as the Laramide Orogeny that created the Rockies happened about 800 miles inland. The idea is that for some reason about 80 ma the pacific plate scooted under the lighter continental rocks before diving. The Rockies came up a bunch, the Colorado Plateau, my homeland, not so much.

The Rockies are now sitting still but the plateau is moving clockwise, pulled by the pacific plate sliding north against and under the north american plate at the continental boundary, as things should happen. The Basin and Range province, Nevada mostly, is being pulled apart. For some reason the Colorado Plateau wants to stay in one piece while western Utah, Arizona, and Nevada are coming apart.

All this motion is happening at about the rate your fingernails are growing. It doesn’t seem like much, but after a few million years we are talking big moves. Stay tuned.

My favorite book on these topics is Annals of the Former World, by John McPhee. It is a big book composed of sections covering the territories along I-80. Great reading.