Western Colorado Road Trip

Recently I had a meeting in Gunnison, so I made a short trip of it. From Denver I went up to Buena Vista and over Monarch Pass, but this time I went over the old Monarch Pass road, abandoned when the highway on upper reaches of the Pass was widened and straightened. Modern mountain highways are expensive, moving mountainsides and filling low spots. The older roads tended to follow the lay of the land more closely. They were cheaper to build but slower and more dangerous.

I like the old roads, even more if they aren’t paved. Old Monarch Pass follows the recipe. It’s narrow, winds around and goes up and down. It had about three inches of partially melted snow, making for some slick spots and lots of mud, but not the mud that likes to trap unsuspecting cars. I was going slow, so I got to enjoy the scenery and a pretty day. I rolled the windows down, opening up my steel cocoon a bit. Good thing.

I like the old roads, even more if they aren’t paved. Old Monarch Pass follows the recipe. It’s narrow, winds around and goes up and down. It had about three inches of partially melted snow, making for some slick spots and lots of mud, but not the mud that likes to trap unsuspecting cars. I was going slow, so I got to enjoy the scenery and a pretty day. I rolled the windows down, opening up my steel cocoon a bit. Good thing.

I stayed in Gunnison, and next morning I drove up to Crested Butte, one of my favorite ski towns, with some of the flavor of an old mining town remaining, in contrast to the modern European Chalet style of Vail. No McDonald’s, no chain restaurants, and lots of local businesses. I had coffee in a place without WiFi.

Next was Kebler Pass, one of the best drives in the state. It goes from Crested Butte to east of Paonia, and is mixed gravel and pavement. If you want the best fall aspen viewing in Colorado, Kebler Pass is the place. Huge stands of quakies with good mountain backdrops. The leaves were gone on this trip, but the beauty remains. To the south are the West Elk mountains and and a large, mostly untraveled wilderness area. The Elk Mountains are North and east, some of the wildest peaks in the state.

I was in big, beautiful, rugged country mostly empty of human development. Emptiness and solitude, part of why I love Western Colorado. The road comes out outside of Somerset, a coal mining town between Paonia and McClure Pass above Carbondale. Big coal mines there, mostly shut down. That’s mining in Colorado. Dig lots of stuff, then go broke and leave a big mess behind.

I like Paonia, fruit trees below mountains, no McDonalds, no Walmart, as it should be. There is lots of pretty farm country from Paonia to the turnoff to Grand Mesa outside Delta. The Grand Mesa road climbs to the top of the 10000 foot tall flat topped Mesa. It’s wet country, catching the storms coming across the desert country to the west. My main memories are going fishing there with my father. Lots of lakes, mosquitoes, gnats, and

cold nights. I did not become a fisherman. The Land’s End road runs west from the highway to the rim of the Mesa. The view is unsurpassed. The San Juan’s to the south, the Uncompahgre Plateau across the Gunnison River valley to the west, and the Grand Valley of the Colorado under the Bookcliffs and the Roan Plateau. You can see into Utah. The road winds off the Mesa to Whitewater. Steep and twisty gravel. I’m saving that part for next time.

I went on over the mesa to Collbran, where I continued my search for the big landslide off the mesa that killed three men running a mile off the mountain. I didn’t find it, but ran round some nice farm and ranch country while looking. When I got home I printed out a map. Duh.

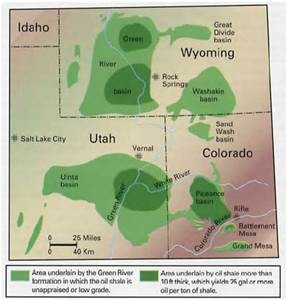

That night I stayed in Parachute off I-70 in oilfield country. Enough about that. Next day I followed the Colorado River from Dotsero to Highway 40 at Kremmling. Again, I crossed a lot of wild country with a bit of development in spots. The river runs in a succession of canyons and narrow valleys. No spectacular mountains, just lots of good rugged country.

After Kremmling, Highway 40, Granby, Winter Park, and Berthoud Pass to eastern Colorado, and home.