Draining the Colorado Plateau

About 600 Million years old, the Colorado Plateau has been relatively stable throughout it’s history. It has uplifts, interesting laccolithic mountains, lava flows, and In the last six million years or so, produced some of the most spectacular scenery on the earth. Canyons. Many canyons carved into many layers of rock, much of it red. The canyons grew upstream from the Grand Canyon, the most spectacular of the canyons.

The Plateau is big, about 130,000 square miles. It could swallow some of those little Eastern states with hardly a belch. Utah east of the Wasatch mountains just east of Salt Lake. Colorado west of the Rocky Mountains, south of the Uintah mountains and north of that rough country in northern New Mexico and Arizona.

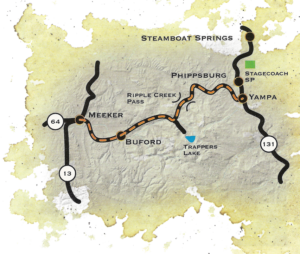

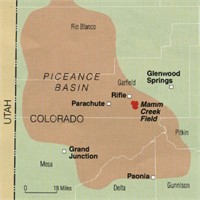

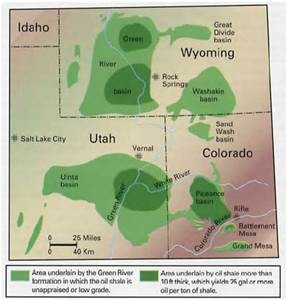

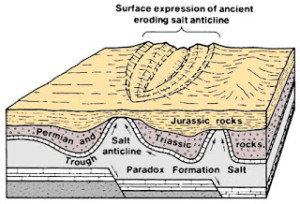

For much of its history the Colorado Plateau was drained interiorly, no outlet to the oceans and surrounded by highlands. The rivers then flowed north from now gone highlands in Arizona into a succession of mostly fresh water lakes. The lakes left signatures such as the Green River Formation with its oil shale and landslides. The Piceance and Uinta basins are examples. I grew up on a margin of the Piceance Basin.

Around six million years ago, the Colorado River flowed south, found its way onto the Basin and Range Province and eventually to the Gulf of California. It is ironic such a powerful river responsible for carving all those canyons seldom reaches the sea, diverted onto land by recent despoilers, us. The shift from internal drainage to the Colorado River with all the canyons carved by the river and tributaries is something of a mystery.

The answer is elevation change. The Colorado Plateau ended up higher than the Basin and Range province to the west. Was the Plateau uplifted or did the Basin and Range subside? The change in elevation is relatively recent and gave the Colorado River the opportunity to begin draining the Plateau.

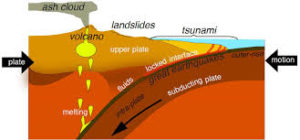

The Basin and Range is known as an extensional region. As the Pacific Tectonic Plate slides northward along the North American Plate, it is stretching and pulling the Basin and Range to the west. As it pulls apart, some big blocks stay at about the same altitude while adjacent blocks drop down to fill the void. Thus we have basins and ranges. There are theories that the entire province subsided as well.

This is probably not the case, as the crust under the region is thinner, a function of stretching, not uplift. With uplift, we would expect the crust to be thicker. The crust is thicker under the Colorado Plateau, suggesting uplift created by the remnant of the Farallon Plate subsiding and allowing lighter rock to rise and allow uplift.

I won’t go into detail about the various layers in the crust responsible for all this. It is complex and all the stuff is way down there. Some are thicker, some thinner, as some rise their chemistry and density changes, and my eyes start glazing over. Take it this way, that big thick and somewhat dense Plateau has stayed in one place and has had several periods of uplift.

The most recent uplift left the Plateau higher than the Basin and Range. A stream on the western margin cut its way into the highland to the east and the Plateau started draining through the new canyon. What a canyon it is, 6000 feet deep. As the river cut its way down, all the tributary streams followed suit by making their own canyons. The region is arid and has lots of cliff forming rocks, so deep, narrow canyons formed, some so narrow you can stand on the bottom and touch each wall.

I wanted the Basin and Range to sink, but is too thin and lightweight so it stretches. The Colorado Plateau is also being pulled by that Pacific Plate, but instead of stretching, that big thick slab is rotating clockwise. I am going to dig around and try to figure out why the Plateau stays in-one piece with all the activities going on all sides, but it is for later. My working hypothesis is since the Colorado Plateau houses the center of the universe, it has stayed intact out of respect.