Four Wheeling for 65 Years

My first four wheeling memory is from deer hunting season somewhere in the early 1950’s. We were staying at a neighbor’s ranch near Douglas Pass with a large party. We went up a creek in a WWII surplus Jeep. There must have been eight or ten people on and in that Jeep. We got up high on a rough road and a front axle broke. I was too young to know much of what was going on, but I did know the Jeep was broken and we were a long way from the ranch. A couple of the men were pretty handy and managed to pull the broken axle with a Crescent wrench and a screwdriver, all the tools they had. My father was impressed and we made it back to the ranch.

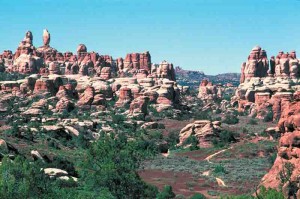

Other four wheeling trips were to what is now Canyonlands National Park. I don’t remember whose Jeep we were in, but we four wheeled over Elephant Hill into Chesler Park. The Elephant Hill road is still open, but Chesler Park was closed to vehicles many years ago. My father didn’t have a four wheel drive in those years, but we went places in our 1953 Chevrolet pickup that are considered four wheel drive only these days. Many of the roads were to fishing areas on Grand Mesa.

There just were not many four wheel drive vehicles in those days, so people made do. In the Bookcliffs area, famous for slick shale roads, there were many hills with a pile of rocks at the bottom of the grade. People stopped, loaded the rocks into the bed of the two wheel drive pickup for weight, and climbed the hill and went where they wanted to go, and unloaded the rocks on the way out.

Army surplus Jeeps became fairly common in the 1950’s, but they were fairly primitive. 35 miles per hour was about what they would do on the highway unless the owner added a Warn overdrive. They also broke a lot. I remember walking home from across the river from Fruita when the steering linkage fell apart on a surplus Jeep.

Later, in the 1970’s, four wheel drive vehicles became more common. New and modernized Jeeps, International Scouts, Broncos, Blazers, and four wheel drive pickups became fairly common. My father had two Scouts, an early Jeep Cherokee; and his first four wheeler, a 50’s Jeep wagon with a Chevy small block V8.

The first Scout got us into trouble on Elephant Hill. We were coming out after dark and as we got to the top of the hill, bouncing over the slickrock, the engine quit. It would not start, so we walked the four miles or so to the Canyonlands Resort. At that time the owner flew tourists over the canyon country, ran the resort, and flew the occasional polygamist away from the law. We waited for him to finish an enormous plate of venison and biscuits, got into his big Ford ¾ ton pickup, and went to the Scout. He towed the Scout about 50 feet and it started. The carburetor float must have stuck and the bouncing knocked it loose.

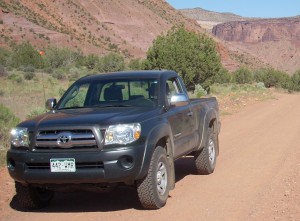

When I started buying four wheelers I got Japanese pickups. They cost less, are reliable and capable, and after all, a feller needs a truck. I just don’t like buying lots of gas for a truck. My current ride is a 2009 Toyota Tacoma 4 cylinder standard cab. Toyotas have grown, it barely fits in our new 20 foot garage.

There are two basic types of four wheelers. There are those who four wheel to go to interesting places that require four wheel drive, and those who enjoy the sport of going to difficult places. There is overlap, but those lifted and modified vehicles are for hard core wheeling and showing off. I have a four wheel drive pickup to go places. My Tacoma is stock.

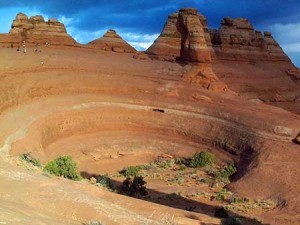

Southeastern Utah is a favorite destination for both types of four wheelers. The Moab Rally every spring brings hardcore rock crawlers from all over the country. There is so much to explore that is accessible because the uranium boom of the 1950’s brought about much road building into areas that had been horseback only.

My favorite area is the Maze District in Canyonlands National Park. 70 miles of dirt road to the ranger station, then many more miles of four wheel drive to places like the Doll House, which has access to the Colorado River just below the confluence with the Green.

This summer seems to be devoted to going over passes. I won’t name them all, but the next one is Pearl Pass. My 12 year old grandmother drove a team and wagon over that pass in 1887. I am a bit older and my team is motorized.