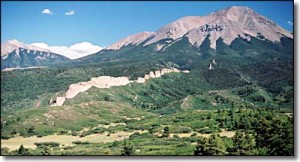

Spanish Peaks and a Dike

I went on a tour of Southern Colorado’s Highway of Legends with a group from Colorado’s Cherokee Trail chapter of the Oregon California Trail Association. Berl Meyer, our chapter president, summers in Cotopaxi, on the Arkansas River. He rambles around Colorado looking at the geology and the mountains. He is from Kentucky, so has a need to get away from relentless green.

Berl organized the trip, having us meet in La Veta. For me the trip had two segments. Colorado geology is one of my interests, and the Highway of Legends country has some world famous geology.

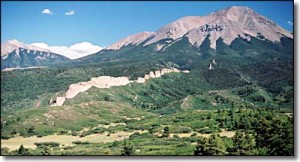

The Spanish Peaks south of La Veta, are relatively recent (geologically) igneous intrusions that rise to over 12,000 feet in elevation. Located fairly far east for the Rockies, they served as important landmarks for early explorers and travelers. When the intrusions barged in, they bulged and fractured the existing rock layers, and a series of vertical dikes radiate from the mountains.

Cucharas Pass is between the Spanish Peaks and the Sangre de Cristo mountains. At 9,995 feet, it is another lovely Colorado mountain pass. There are lots of dikes, and on the south side of the pass is Stonewall, at first look another dike, but this feature is a vertical wall of Dakota sandstone, pushed on edge by the Spanish Peaks uplift.

We had a startling encounter at Stonewall. We had stopped for a break and to look the stone wall over when we had a visit from a Greek god. Most people don’t know, but the gods are still with us. They travel the world keeping track of events and people. This particular Greek god is one of the lesser ones, namely Hermes’ great uncle. The photo shows him as he was leaving.

We had a startling encounter at Stonewall. We had stopped for a break and to look the stone wall over when we had a visit from a Greek god. Most people don’t know, but the gods are still with us. They travel the world keeping track of events and people. This particular Greek god is one of the lesser ones, namely Hermes’ great uncle. The photo shows him as he was leaving.

The road then enters the coal country west of Trinidad. There is lots of history in that area, and a world famous geological feature. On the road to Trinidad Lake just outside Trinidad is an exposure of the K-P (formerly K-T) boundary that marks the end of the Mesozoic era and the beginning of the Cenozoic, or modern era. It is called the K-P because it is the boundary between the Cretaceous period and the Paleogene period. Below the boundary, dinosaurs. Above the boundary, no dinosaurs.

The boundary is a narrow band of whitish clay that fell when an asteroid struck off Yucatan and threw a tremendous cloud of material into the atmosphere, blocking the sun and cooling the entire planet. 75% of life on earth perished, including the dinosaurs. In a road cut on the way to the lake you can put your hand on the boundary.

There are exposures in many places around the world, including North Table Mountain in Golden, but this one is the most accessible. I have wanted to go there for a long time.

We went to the San Luis Valley, over La Veta Pass from La Veta. The valley is our own rift valley, formed as the movement of the Pacific tectonic plate drags some of the North American plate north. The motion pulls things apart, and a big block subsided, forming the rift valley. The Arkansas River north of Poncha Pass and the Rio Grande River mark the rift. (Real geologists, including Berl, don’t get the vapors at this explanation.)

Great Sand Dunes

On the east side of the San Luis Valley is The Great Sand Dunes National Park, another world famous geological feature. The sand for the dunes comes from the San Juan Mountains to the west. Normally, the sand would just keep going, blown over the Sangres to the plains farther east. In this case, a creek picks up the sand blown off the dunes and carries it back to the other side, replenishing them every spring. The result is a mammoth dune field, good for viewing, climbing, and tumbling down. The creek is good for play as long as it lasts into the summer.

Good geology, good scenery, and a good time. The geology is not a legend, however. It is the real thing, and students from geology departments all over the country visit and study in Colorado.