The Colorado Plateau Part One

I am a child of the Colorado Plateau. I was born and grew up in Fruita, Colorado, and still think of Fruita as home, although I have lived along the Front Range of Colorado most of my life. The Grand Valley of the Colorado River is near the Grand Hogback, the eastern extent of the plateau in that area. The Grand Valley is green due to irrigation, but the annual precipitation averages around eight inches a La year, fairly typical of the Plateau.

I am sure that the center of the universe (well, my universe) is somewhere within 100 miles from the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers. It is fitting, therefore that the Plateau is somewhat unique geologically. All those striking layers of varicolored rock formed into spectacular scenery by the work of the Colorado River and its tributaries are relatively undisturbed compared to the Plateau’s neighbors, the Rocky Mountains, the Basin and Range, the Wasatch and Uintah mountains and the Mogollan Rim in Arizona. Pretty neat neighbors, eh?

Those places have been folded, faulted, stretched lifted, collapsed, and otherwise deformed. The Plateau, on the other hand has remained relatively stable through much of geologic time. It is this big slab, poked, lifted, twisted, drowned, buried, and eroded several times but still mostly intact. There were just enough deformation and intrusion to make things interesting.

The reasons for this stability are still somewhat controversial, bit have to do with the Pacific Plate coming our way and north at about the rate your fingernails grow, and the North American Plate headed west at about the same speed. At different times they have behaved in different ways that, coupled with the somewhat thicker crust under the Plateau, have resulted in this unique region. I don’t have the space or understanding to explain all those processes, but we can see the result.

An interesting fact is that the entire plateau seems to be rotating clockwise as the Pacific Plate grinds along northward. That movement is also what is pulling the Basin and Range province apart. Don’t look for any big changes next week. This process is really slow. While all this plate movement is going on, our friends the Green and Colorado rivers just keep digging. On rare occasions you can see the digging, when there are exceptionally big thunderstorms during the summer monsoon. A lot of stuff goes into the rivers then. Today, Lake Powell is catching it, and will become one huge mud flat until the dam eventually fails.

Looking at all these processes requires a different sense of time than how we live from day to day. In geologic terms, sixty million years (60ma) is relatively brief. We think of our world as stable (unless you live in the Bay Area) but in truth, everything is on the move, it is just a bit slow.

The Colorado River will eventually bring the entire plateau down to sea level. Look at Grand Canyon or any of the tributary canyons to see how it works. My favorite is the San Juan. Some fine canyons and not as cluttered up with people. Another place to see the processes of change is Upheaval Dome in Canyonlands National park. A great big rock came along and smashed down, forming a huge crater and shaking everything up for a long way around. You can see rocks turned to waves from that hit all the way to Dewey Bridge.

That big crater tried to form a lake, but it is dry there. The water did make its way to the river, cutting as it went, and now the crater has an outlet. The crater will get bigger as the cliffs erode back until it is just a depression, then, gone.

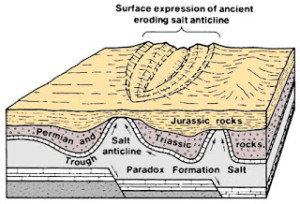

There is a plug of gypsum in the crater. When all that rock was blown out by the impact, the pressure on the stuff under the crater was lowered. Some of that stuff down there is salt, known as the Paradox Formation, which can flow. The salt goes into the river, but gypsum isn’t quite as soluble and there it is. The salt is from an ancient sea that alternated between filling and drying up as sea level rose and fell. That left a lot of salt which was then buried under a lot of rock.

That salt moving around and being dissolved is responsible for much of the scenery in the Moab and surrounding areas. As it dissolves, some of the overlying rock drops down, creating some fairly large valleys. Paradox Valley, Sinbad Valley, Lisbon Valley (uranium, oil, and gas), Spanish Valley (Moab), Castle Valley, Fisher Valley, are all big grabens. They are big blocks that dropped down as the salt leached away. Paradox Valley and Spanish Valley have rivers coming out of a canyon on one side, and going across the valley into a canyon on the other side. Moab has the Colorado, Paradox has the Dolores. That makes for some fine scenery.

The fins and arches in Arches and Canyonlands come from the same process on a smaller scale. All that magnificent scenery is a result of that ancient sea floor full of salt being buried by a colorful succession of rocks that the rivers and the wind could work on.

An exception to the salt influencing the process resulting in fins and arches is Rattlesnake Canyon in Colorado near Fruita. The river is solely responsible for the work. The arches are just as cool, and not all full of people.

Next time, some of the other interesting things about the Colorado Plateau, one of the most interesting places on the planet.