Colorado’s Front Range Floods

Those of us who live along the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains enjoy a unique set of circumstances; a fine climate, mountain views, a mountain playground, and rivers that provide much of our water needs. There are millions of people living in an urban area that runs from Pueblo to Fort Collins.

Most of the time, the physical setting and the climate combine to make the Front Range a fine place to live. There is risk, however. Most of the time we don’t have quite enough water for every need. The people are along the Front Range, and the water is on the western slope. On occasion, we have way too much water. We are subject to drought, our own waste of the water we have, and the floods that come out of the mountain canyons.

To understand these problems requires a look at two histories, the Rocky Mountain history for the last 75 million years and human history from 1859. Around 75 million years ago the Rockies began to form. As they grew, they also wore down. The debris from the mountains spread from their base to as far as Nebraska.

The streams were bigger then. Drive east to Bijou Creek and see the valley that obviously was not formed by the current flow in the creek. The wind blew. It still does, leaving eolian sand deposits. Sand Creek, draining the area east through Stapleton and into Aurora is appropriately named. You can identify the sand hills – they are grazing land, not good for farming. That sand and dirt comes from as far as Utah and coats our cars.

Today, the Rockies are not eroding as fast as they did during the ice ages, but they are still coming down. Back in the Precambrian when I took geology, the assumption was that erosion was a steady, gradual process. Taking the long view, that is so, but on a human time scale, erosion is punctuated by periodic floods. Some of the floods are from spring runoff from wet winters. The catastrophic floods pound out of the canyons when storms park themselves over an area and it rains. And rains. Sometimes it rains more in a few hours than it does in several normal years. Sometimes the rain is where the people are, just east of the mountains.

Large amounts of moist monsoonal air from the Gulf of Mexico move north along the Rockies and encounter a cold front coming from the west. Sometimes the rains are short in a fairly small area. At other times, as in 2013, the rain comes down over a large area, and it rains for days. To humans, these storms seem like unusual events, but they have been happening for millions of years. Along with normal erosion, they have filled the Denver Basin with 13,000 feet of debris. That is a lot of rocks and mud.

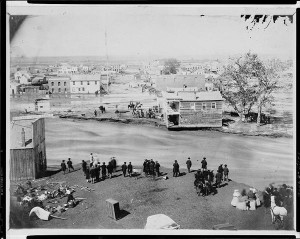

One of the first recorded monsoonal floods was in 1864, not long after Denver was settled. Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians told the settlers seeking fortune not to build where Cherry Creek and the South Platte meet. The town builders built there anyway. It was a logical town site. Trails met, grass, trees, and water were available, and the gold-rich mountains just a short distance away. Much of the new town went downstream.

The town was rebuilt in the same place. Floods came again. Denver flooded in 1876, 1885, 1894, 1912, 1921, 1933, and 1965. Pueblo flooded in 1921, the Big Thompson in 1976, Manitou Springs and Colorado Springs in 2013, and much of the Front Range from Denver to Fort Collins in 2013. The link is from the Atlantic Monthly, with dramatic images from the 2013 flooding.

Most vulnerable are towns at the base of the mountains: Manitou Springs, Palmer Lake, Morrison, Golden, Boulder, Lyons, Loveland, and Fort Collins. Towns along the South Platte, St. Vrain, Cache La Poudre, and Big Thompson rivers are at special risk.

Will people stop building there? Rebuilding is underway in every area flooded in 2013. While researching this piece I traveled to Boulder, Jamestown, Lyons, and the farmland along the St Vrain. I saw travel trailers parked nest to damaged homes with building permits on the flood-damaged houses.

Some actions do prevent floods. Denver has Cherry Creek, Bear Creek, and Chatfield dams. They are flood control dams designed to capture floodwaters. Let’s hope they are big enough.

The photo above has a lot of rock in the foreground. The rocks range in size from sand and silt to head size. They were exposed by the 2013 flood, but were deposited by a previous flood that had enough force to carry that debris and dump it there. upstream, there are narrow gulches with the lower ends scoured down to bedrock. That debris went further downstream.

The Rocky Mountains are on the way to the Mississippi river delta in Louisiana. It will take many millions of years, but they will wear down and become Mississippi mud. Floods will hasten the process.

Howdy our significant other! I have to express that this article is incredible, great composed and can include about just about all substantial infos. I’m going to view further content like this .