The Colorado Plateau Part Two

There is a lot of beautiful country on the Colorado Plateau, but there is the other side. The term many use is the stinking desert. My home town has an annual rainfall of about eight inches. Before the Utes were run out and ditches were dug, the Grand Valley was a sparse desert. The irrigation projects made much of the valley green, but north of the Highline Canal is the desert. It is a fairly barren desert, not like the Sonoran Desert with its green saguaro cactus.

The soil, if you can call it that, is fairly infertile, high in salts, and high in toxic selenium. It’s called the Mancos Shale. The Mancos Shale, called the Pierre Shale east of the Rockies, runs from South Dakota to central Utah. It is an ancient sea floor, Cretaceous in age, of the inland sea covering much of North America. Shale is mud rock, laid down as the sea advanced and retreated over millions of years.

The lower part of the Bookcliffs and the valley floors are Mancos Shale. In its natural state it is a scrub grassland, supporting small populations of deer, antelope, prairie dogs, sage grouse, cottontails, and some Bison. When the Northern European Americans arrived, they saw grazing land. The sheep and cattle came. The ranchers did well for a few years, but their expectations were unrealistic for such a dry area. Soon, most of the good grass was gone, replaced by cheat grass and sagebrush.

The area between Delta and Grand Junction is a prime example. My father, born in 1903, lived in Grand Junction after 1918. He told me that at that time, there were extensive stands of tall bunch grasses. They are gone. That desert is one of the most barren stretches I am aware of. It is hilly, so irrigation water went to flatter areas. It is close to towns, so lots of ranchers grazed their stock on the land.

Much of the Mancos shale country is BLM land today. In the old days, the Land Office and the Grazing Service leased land to ranchers. There were allocations on the number of head allowed on each segment, but there was little enforcement. The grass mostly disappeared. Thus, the stinking desert.

I-70 from Palisade to the west of Green River, Utah is on the Mancos. Highway Six from where I-70 veers south almost all the way to Price is on the Mancos. Travelers on those highways have the bare Bookcliffs and the bare desert floor to look at for over 200 miles. Their impression was what tended to keep the canyon country to the south relatively isolated. Locals had all that magnificent country mostly to themselves.

The a uranium and oil and gas booms of the 1950s built a large network of roads and opened the canyon country up for tourism. Those flat deserts remain empty, along with the mostly shale country of the Bookcliffs and the Tavaputs Plateau to the North.

When I went to Arches in the 1950s, we drove down two tracks winding through the sand. This year during the height of the season, cars were lined up literally for miles. Canyonlands National Park is also crowded, people lined up. I remember going there and often seeing no one.

From Green River to Hanksville is mostly flat, dry desert, with 70 miles from the highway turnoff to the Maze District Ranger Station in Canyonlands. The greater part of Navajo country in southern Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona is fairly flat desert. Monument Valley is flat desert that happens to have some rocks sticking up. Have you ever driven from Albuquerque to Flagstaff on I-40? Flat desert.

The Colorado Plateau does have some other features. Mountains, tall, green, and wet, supplying water to the desert. Three ranges of mountains, the La Sals near Moab, the Abajos, known to locals as the Blues, and the Henry Mountains, near to nowhere. The La Sals are the tallest, over 12,000 feet. The Abajos and the Henrys stretch to 11,000 feet. They stand in contrast to the red rock country surrounding them, and provide a welcome relief. People go there in summer to cool off and enjoy the wildlife.

Geologically, the mountains are Laccoliths, formed by a neck of molten magma rising to a weaker junction between two layers of sandstone. At that junction the magma moves laterally, forming a mushroom shaped dome of igneous rock in the domain of sandstone. The overlying strata usually erode away, leaving the igneous core. The Henrys are the type location for Laccoliths, being the subjects of the earliest study, and displaying the domed shape.

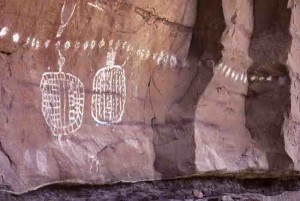

The three ranges are important to ranching, providing water, hay farming, and a summer range, with the stock wintering on the desert. Salt Creek, draining north from the Blues, has a canyon with year-round water, arches, and Ancestral Puebloan ruins and rock art. The canyon also provides access to a park in the midst of the Needles District of Canyonlands. I like that park because it was never grazed. It provides a look at the land before cattle came, trampling or eating everything, mangling stream banks, and bringing alien species like cheat grass. No I won’t tell you where it is. Go look for yourself.