Kodel’s Canyon

In the late 1950’s, some friends and I liked to go to Kodel’s Canyon. The canyon is in the Colorado National Monument about five miles from Fruita. We would get a ride from a parent and with our .22 rifles, hike on the relatively flat desert area between the Colorado River and the National Monument, laying waste to any number of unsuspecting rocks with our .22’s.

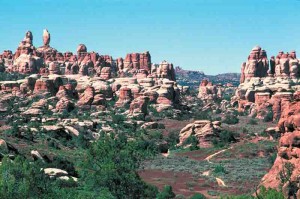

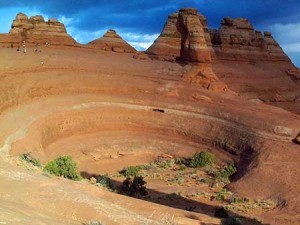

Sometimes we would climb over the Park boundary fence and up into the canyon. It is the first canyon west of Fruita Canyon, where Rim Rock Drive climbs, and the scenery is as spectacular as the rest of the National Monument, but at the time was seldom visited. Carrying firearms into the National Park and firing them was illegal, but we never worried about getting caught. No one went there but the local kids.

The canyon has the sheer sandstone cliffs the Monument is famous for, but the lower end is black Precambrian granite, schist, and gneiss, black and weathered into narrow cracks and rounded humps. A demented miner who gave the canyon its name worked a mine in that rock for many years, never finding any gold. It should have been clear to him there was no gold; there is relatively little quartz in the rock, which is associated with gold, and Kodel’s canyon is far from the Colorado Mineral Belt, which runs from the Golden-Boulder area to Telluride. Most of the state’s minerals, including gold, are in that roughly 20 mile wide belt. The big exception is Cripple Creek, a volcanic neck with a rich gold deposit. Nevertheless, Kodel persisted for years, giving the local Fruita kids a place to risk their lives.

We would poke around in the mine, and its mystery. We didn’t go too far in, as we never had a flashlight. The big attraction was the climbing. In some places the 1.4 billion years old rock is broken and crumbling, but for the most part is so smooth and rounded as to look polished.

We had no climbing shoes, just our tennies. We had no helmets, ropes, or the hardware climbers use today. We got good at mostly unaided climbing and went up places that trained climbers attempt only with ropes and hardware. The only climbing aids we used were our .22 rifles, using them to help one another up especially steep pitches or as support. The climbing was somewhere between bouldering and free soloing. Not for those afraid of heights.

Years later, I climbed Long’s Peak with some friends. Lee had a bad knee, and Danny was helping him as we went up the Cable Route, which traverses the top of The Diamond, that sheer northeast face of the mountain with a 2,000 foot high cliff. Years ago the route had a fixed steel cable leading to the top that climbers could hold on to. When we climbed, there was no cable and some of the rock was wet. I just climbed up, doing what I learned in Kodel’s Canyon.

Danny would move up a pitch with the rope and belay Lee as he climbed on that bad knee. Danny remarked to Lee as they crept up with their rope that I was single-handing. It was steep, but I had good shoes and walked up, using one hand to occasionally support myself as I chose each foot placement. Proper safe climbing technique calls for having three support points on the rock, moving one hand or foot at a time. I was not ignoring the rule, I didn’t know it existed.

I only know of one serious injury in Kodel’s Canyon. Jerry badly sprained an ankle on the approach to the canyon and had to have help getting back to the road. He hobbled around for weeks, not getting much sympathy from us. In retrospect, we were serious risk-takers, but we just went where we wanted to without thinking about the danger. Those experiences in the hills and canyons south of Fruita made us all willing to accept challenges with little hesitation. We also gained confidence in our ability to overcome difficulty. We acquired life skills there. In our safety-oriented society, kids may be missing some important lessons. We need to test ourselves in the name of fun, and risk is part of the test. For me, it was a fun thing to do. I think I will go back, a bit more carefully this time.